💧 The Elusive Element: Why Moisture is So Critical

In the world of composting, we often talk about the Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C:N) ratio and aeration. But there’s a third, equally critical factor that determines success or failure: moisture content.

The beneficial aerobic bacteria and fungi—the tiny workers who break down your kitchen scraps—are living organisms, and they need water to survive, move around, and perform their metabolic processes.

Too little moisture, and your pile will stall out entirely. Too much, and it quickly becomes a stinky, anaerobic mess. Finding that sweet spot is key to producing ‘black gold’ quickly and efficiently.

📏 The Golden Rule: The Wring Test

While lab science might measure moisture content at a precise 40% to 60%, home composters rely on a much simpler, tactile test that works every time.

The Wring Test Method

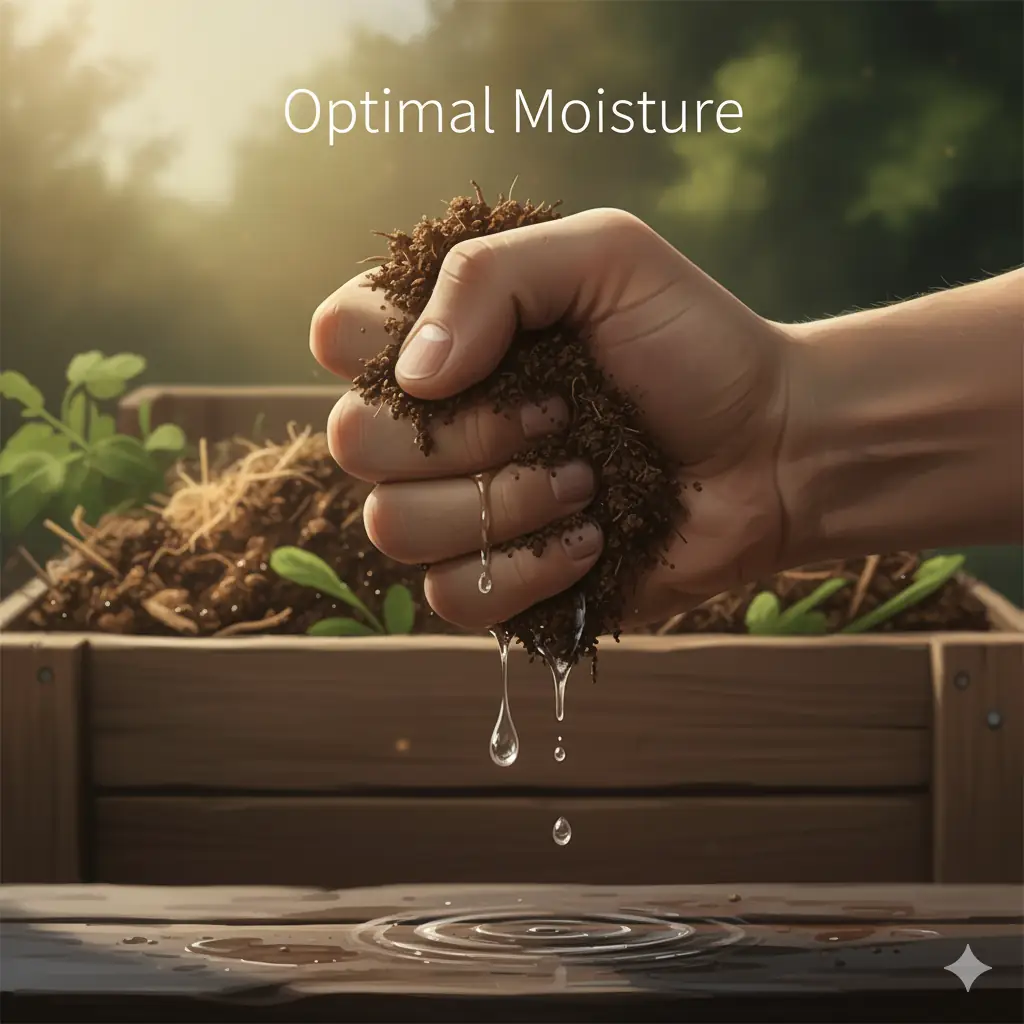

Grab a handful of compost material from the center of the pile and squeeze it tightly. The compost is at the ideal moisture level if:

- It feels damp to the touch, like a used kitchen sponge.

- Only one or two drops of water drip out when squeezed hard.

If you get a stream of water, it’s too wet. If your hand stays dry and the material crumbles, it’s too dry. This simple test is your best diagnostic tool.

🛑 Problem 1: The Pile is Too Dry (Stalled Out)

A dry compost pile is a sleeping compost pile. Microbes go dormant when the moisture content drops too low, halting all decomposition. This often happens in hot, windy weather or when a pile is built primarily with dry ‘Browns’ like paper or sawdust.

Diagnosis:

The pile is cold, dusty, smells like dry earth, and looks exactly the same as it did weeks ago. Nothing is breaking down.

The Fix: Hydrate and Turn

- Water Thoroughly: Use a hose with a spray nozzle or a watering can to moisten the pile.

- Turn to Mix: As you water, actively turn the pile with a fork or aerator. This ensures the water penetrates the entire mass, not just the outside layer.

- Recheck: Stop adding water when the material passes the wring test.

This simple act can wake up a stalled pile, often causing it to heat up significantly within 24 hours as the microbes spring back to life.

⚠️ Problem 2: The Pile is Too Wet (Stinky and Slimy)

Excess moisture is the number one cause of bad smells. The water fills the necessary air gaps (porosity), causing the beneficial aerobic bacteria to drown. Slow, smelly anaerobic decay takes over.

Diagnosis:

The pile smells sour, rancid, or like rotten eggs (ammonia). It feels heavy and dense, and water may seep out the bottom when you disturb it.

The Fix: Absorb and Aerate

- Add Dry Browns: The fastest way to absorb excess water is by adding dry, absorbent ‘Browns’—shredded paper, sawdust, wood shavings, or dry leaves.

- Turn Vigorously: Mix the dry materials throughout the wet zones of the pile. This dual action absorbs liquid *and* creates new air pockets simultaneously.

- Cover Up: If rain is the issue, cover your bin with a tarp or lid to prevent further saturation. Ensure the bin has working drainage holes.

Notes:

- Source Control: If you add very wet materials like fruit pulp from juicing, always drain them first and immediately cover them with three times the volume of dry carbon.

- Location: If your bin sits in a low spot where water pools, move it to a higher, better-drained area to prevent constant waterlogging.

🔄 Prevention: Building Moisture Management In

The best way to manage moisture is to build your pile correctly from the start, making it resilient to weather fluctuations.

Layering Strategy

Maintain that layered approach: every batch of wet ‘Greens’ (high moisture) must be immediately sandwiched between thick layers of dry ‘Browns’ (absorbent carbon).

This ensures the moisture is distributed evenly, rather than sinking to the bottom and creating a dense, rotting base layer.

Structural Integrity

Always include bulking agents like wood chips or straw in your pile. These materials physically hold the compost apart, preventing compaction even when moisture levels temporarily rise.

The microbes in your pile require a thin film of water around their bodies to absorb food and move. If the film is too thick (too much water), oxygen can’t pass through; if the film is gone (too dry), they can’t eat. Optimal moisture ensures perfect gas exchange.

🎉 The Payoff of the Perfect Balance

Mastering moisture management is truly the hallmark of an advanced composter. It means your pile operates efficiently, regardless of what you toss in or what the weather does outside.

By consistently checking for that ‘wrung-out sponge’ feel and using absorbent materials as your defense, you’ll ensure a continuous supply of rich, odorless, and perfectly decomposed compost for your garden.